Please read Part 1 and Part 2 if you haven’t already done so.

In this third and final part, I’m going to discuss the specific difficulties faced by learners (and native speakers!) of English when it comes to spelling.

In English, the same sound can be spelt in different ways. For instance, the long -ee sound (iː) can be spelt ee (see), ea (tea), ey (key), ei (ceiling), ie (chief), y (happy), plain e (legal), and even eo in the very common word people. That’s eight possibilities, and there are probably others I’ve missed. There’s almost no logic you can apply here – there’s no rule like “this is a verb, so it must be ie” – so you have to learn the spelling of each word separately. It must be said that English isn’t the only major language with this problem. French also suffers from this, and I’ve heard that Norwegian has numerous ways of spelling the “sh” sound as in ship.

English also suffers from the opposite problem, in that the same letter, or combination of letters, can represent different sounds. This is where English differs from French. If you say a French word that I’ve never heard of, I might not know how to spell it, but if I read a new French word, I’ll very likely know how to say it. English fails, miserably, in both directions. To show you what I mean, take the word dreat. It’s a highly obscure technical term, so you probably don’t know it. How do you think it’s pronounced? To see the problem, here’s someone staying at a hotel, talking about how he plans to start the day:

A full English breakfast with a cup of Earl Grey tea? Great idea.

The ea combination appears five times in the sentence above, and if you listen carefully to the recording, you’ll notice that it’s pronounced a different way every time. (The ea in the word “Earl” is also affected by the following R.)

So how do you say dreat? You might expect it to rhyme with heat. But perhaps it rhymes with great. Or maybe sweat. Or who knows, something else? Here I’ve recorded some possibilities for the pronunciation of this word, and at the end of this post you’ll find out the answer.

Another source of difficulty are double consonants. In fact they’re a real pain. Sometimes double consonants serve a purpose – they can indicate that the preceding vowel is short (as in little), while a single consonant usually follows a long vowel (as in title). Other times, they are created by prefixes and suffixes that modify an existing word, such as in the adverb occasionally, which is formed by adding -ly to the adjective occasional. Occasionally, as with the double N in the word openness, the double letter is actually pronounced as a long consonant. It’s almost like we say the N twice. Much of the time, however, double consonants serve little purpose, as is the case with the double R in embarrass or either of the pairs of double letters in accommodate. Native speakers make mistakes with single and double consonants all the time, so don’t be too concerned if you also have difficulty with them. At the beginning of Part 1, I said that my best performer (so far) in my spelling tests is an Italian guy, and the fact that double consonants are very common in the Italian language might have been to his advantage. (In Romanian, double consonants are pretty rare.)

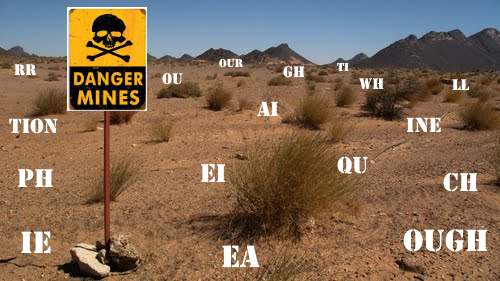

I wouldn’t want to go here. It would make me thirsty.

…and the sign looks so professional.

You saw the word “millennium” everywhere in the UK around the year 2000. Loads of people got it wrong.

Then we have the schwa. What’s a schwa, you ask? It’s a short, neutral vowel sound, which corresponds to the a in alone. In the International Phonetic Alphabet, or IPA, the schwa is represented by ə (an upside-down e). For all you Romanians out there, it’s close to the sound you write as ă, the main difference being that it’s sometimes stressed in Romanian but is always unstressed in English. The schwa seems so harmless, but it’s just as big a source of spelling errors among native speakers as double consonants, and here’s why. The words normal, golden, pencil, bacon and album all have the schwa sound in the second syllable, but in each case the sound is represented by a different vowel letter. You could even include y by adding zephyr (which is a word for a gentle breeze) to the list, giving us six possible representations for the schwa sound.

There are other possibilities too, mainly vowel combinations like the ai in mountain. This is just like the situation with the long -ee sound I talked about at the start of this post, but as the schwa is the most common sound in English (yes, really), I thought it deserved its own mention.

Last but not least, there are silent letters. As the name suggests, these are letters that make no sound at all, like the B in debt and doubt that I mentioned in Part 1, or the W in wrong and answer. Occasionally, like in debt and doubt, these letters were falsely added for etymological reasons, but mostly the letters were pronounced at one time, but aren’t anymore, and (perhaps unfortunately) the spelling hasn’t been updated to reflect that.

This series of blog posts might not have helped you much with English spelling, but I hope they’ve given you a greater appreciation (that’s with double P) of why it’s such a minefield, and make you feel less bad about it if it’s something you struggle with. Oh, and by the way, dreat is word I just made up.